Japanese Female Writers

This post is a list of list of female writers in Japan, which includes authors, novelists, and translators. All the writers listed have been recognized with at least one of Japan’s literary awards, such as the Akutagawa Literary Prize, Naoki Prize, and the Female Writer’s Award. In recent years, more of them have been translated into English, with some that have other European language translations such as French, Italian and German. They are listed by date of birth as the periods in which they live may give some context about their tone or what makes them distinctive for their era. Note that the names written in Japanese have the family first (for example, Momoko Ishii is actually Ishii Momoko with the Japanese characters).

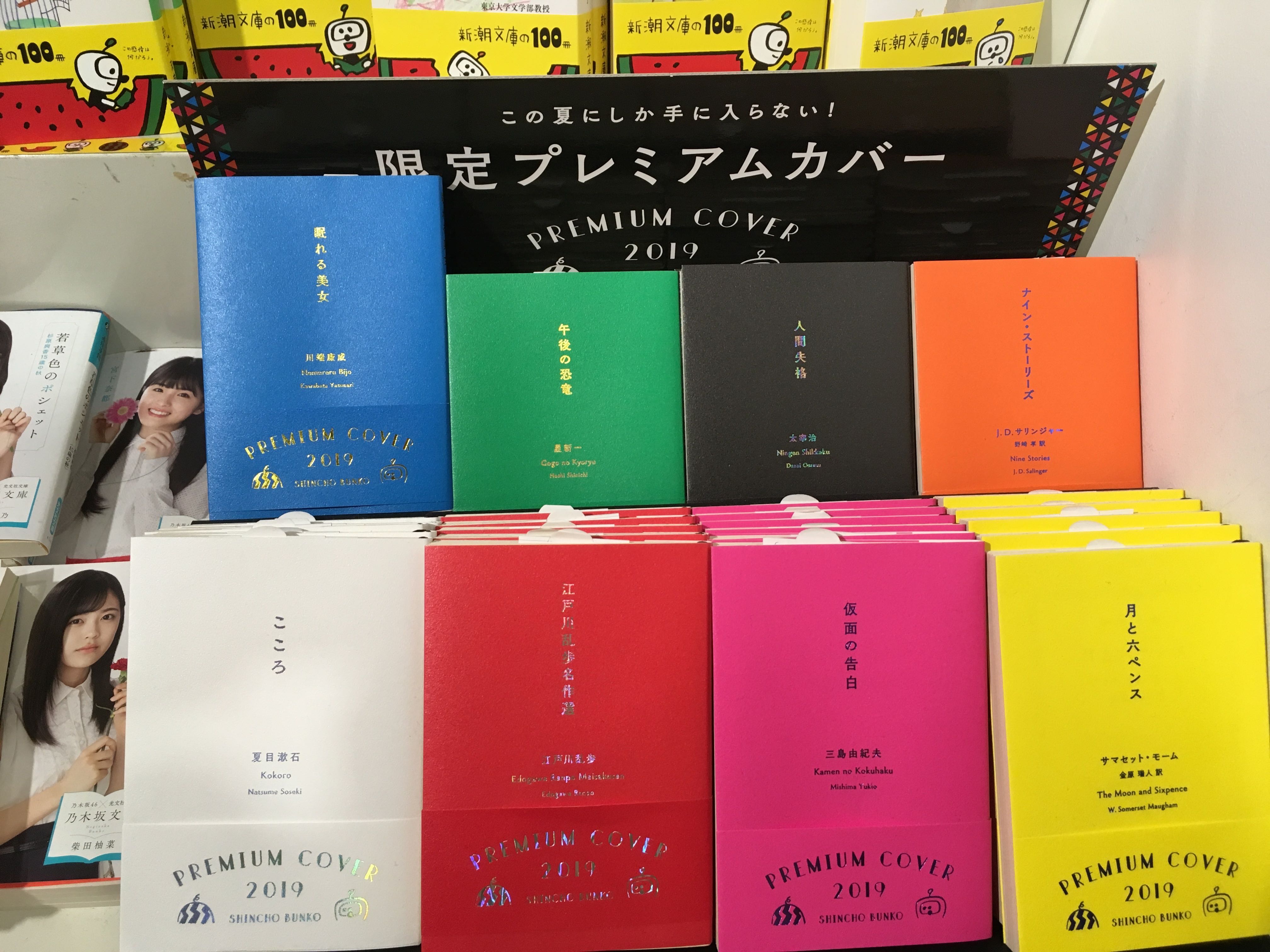

A collection of literary classics, including Japanese and translated writers

Why Female Japanese Writers: The Preamble…

A year or two ago, I realised I was in no position to profess my love Japanese literature, as true as I felt it was. Though I’ve probably read an equal number of Japanese and Canadian novels, all of the Japanese authors until Banana Yoshimoto were male (two chapters of the monolithic Tale of Genji don’t count). Though I enjoyed her book Kitchen enough go through the story in English, Japanese, and Chinese, I had a nagging doubt about whether it was actually ‘good’ writing. By ‘good’ I suppose I mean literary, high literature. Who were the the women I should compare her to? How did they write? Of what did they write? Did they even exist?

I addressed this by looking up a university semester’s worth of writing. The list is happily long, though many have yet to be translated into English. I have also left out some who are well known to the global audience, such as Ruth Ozeki, who has spent significant time in Japan but was born in the US. I would also like to give an honourary mention to Pachinko by Min Jin Lee, who is South Korean-American and has lived in Tokyo.

Free Stories and Podcast Interviews with Japanese Female Writers

If you would like free stories from Japanese writers, here are two short stories:

- ‘See’ by Erika Kobayashi in Asymptote Journal

- ‘Sunrise’ by Erika Kobayashi in Asymptote Journal

- ‘Celan Reads Japanese’ by Yoko Tawada in The White Review (2013)

- “The Far Shore by Yoko Tawada” in Words Without Borders (2015)

- ‘To Zagreb’ by Yoko Tawada in Granta 131 (2015)

- ‘Memoirs of a Polar Bear’ excerpt by Yoko Tawada in Granta 136 (2016)

If you want to find one collection of award-winning Japanese female writers, hunt down the Granta Issue 127: Japan (2014). The collection has a mix of writers, including reknown ones such as Ruth Ozeki and Haruki Murakami, as well as translations from the writers mentioned below.

In addition, you can listen to the Granta Podcast interviews with three female Japanese writers to tie into the magazine’s Japan issue.

Japanese Female Writers

For all its ill repute about sexism and misogyny, Japan has a long tradition of respected female writers. The woman who wrote the world’s first novel, the Tale of Genji, is simply known as Lady Murasaki, after her husband’s family name, but her status in literary history is undisputed. Women’s poems may have been relegated to the phonetic hiragana (in contrast to elevated kanji ones by men), but they were nonetheless included in collections like the Ogura 100 Poems (小倉百人一首), which became the foundation for the competitive card game Kyōgi karuta (競技かるた), now popularised in the anime Chihayafuru.

Based on what little I’ve read, I am tempted to say that the choice of translations seems to follow a similar pattern of what seems quintessentially Japanese: alienation and the relentless monotony of sexist expectations, hyper sexualised stories, and the ‘bizarre’ (not quite sci-fi, but something that requires suspended disbelief). To be fair, since these are all writers who have won Japan’s literary prizes, it may be said that these are styles and topics that Japanese like. Yet, I found myself wondering — what would the female version of Yasunari Kawabata sound like?

The works by Japanese female writers that I have read to date include Sei Shonagon’s Pillow Book, Banana Yoshimoto’s Kitchen and its loneliness_,_ Yuko Tsushima’s Territory of Light and the systemic relentlessness against single-parenthood for a mother with unmaternal tendancies, Amy Yamada’s Bedroom Eyes and its Freudian unleashing of female desire and racism_,_ Hiromi Kawakami’s Tokyo Diaries (in Japanese) for its warmth, and Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko — because Korean zainichi in Japan are part of the country too. What I hope to assemble is a reading list that encompasses Mieko Kawakami’s Osaka working-class experience, Risa Wataya’s youthful voice, and Yu Muri’s experiences as a Korean born in Japan.

Momoko Ishii 石井 桃子

Momoko Ishii (1907 – 2008) is not mentioned by people who make lists of Japanese literature because she is known for her children’s books and translations into Japanese, which I think have not had recent publications. She translated Winnie-the-Pooh into Japanese in 1940, published 19 books of her own and 120 translations for children. In post-war Japan (1958), she used her house to start a library for children called “Katsura bunko”.

Picture books that you can look out for in English include Issun Boshi, The Inchling: An Old Tale of Japan and The Doll’s Day for Yoshiko, though you might have better luck finding them in other language.

Yōko Sano 佐野洋子

Yōko Sano (1938 – 2010) was born in Beijing, China, during Japan’s military expansion from the Korean Peninsula and Manchuria. She is known for many children’s books, but in particular is known for the book, and movie, The Cat That Lived a Million Times. She traveled to Europe in 1967 and studied lithography in Berlin. In 1973 she published her first picture book, Sū-chan to neko (Su and the Cat). She went on to produce various styles of picture books, including Ojisan no kasa (Uncle’s Umbrella), Her book Watashi no bōshi (My Hat) won the Kodansha Award for Picture Books and Nē tōsan (Hey Papa) won the Shogakukan Children’s Publication Culture Award. She also translated books into Japanese and did illustrations.

Kiyoko Murata 村田 喜代子

Kiyoko Murata (1945 – ) won the Akutagawa Prize, arguably the most prestigious literary prize in Japan, as well as other celebrated awards such as the Noma Literary Prize, and the Yomiuri Prize. She is one of the only female writers awarded the Medal with Purple Ribbon, which is given to people who have contributed significantly to artistic and cultural fields (including sports) and her works have been adapted for film by renowned directors like Akira Kurosawa and Hideo Onchi. Unfortunately, I don’t think she is translated into English, yet, though her books have French versions, such as Le Chaudron and Fille de Joie.

Yuko Tsushima 津島 佑子

Yuko Tsushima (1947 – 2016) is the pen name for Satoko Tsushima. She’s a well respected and established writer in Japan and classified as a feminist, though I’ve not read enough of her pieces to know. I read the recent English translation, Territory of Light, which is a short and seering piece that looks at motherhood and the relentlessness of child rearing. You can also check out Child of Fortune and Of Dogs and Walls. She passed away in 2016. She is the daughter of one of Japan’s most well known modern male writers, Osamu Dazai, who killed himself when she was one.

Rieko Matsuura 松浦 理英子

Rieko Matsuura (1958 – ) is a novelist and short-story writer. Her book, the The Apprenticeship of Big Toe P, won the Women Writers’ Prize, Japan’s most prestigious literary prize for female writers. A provocative, picaresque spin on a coming-of-age story, the novel tells of a young Japanese woman who wakes up one afternoon to discover that her big toe has turned into a penis. In learning to adjust to her new sexual organ, the heroine is forced to reconsider her body, her sexuality and her life. After fleeing from her homophobic fiance, she falls in love with a bisexual blind pianist who accepts her for whom she is, and together they join a troupe of performers–all sexually deformed and emotionally twisted men and women. Thus begins her apprenticeship.

Amy Yamada 山田 詠美

Amy Yamada (1959 – ) is a popular contemporary writer known for her blunt depictions of sexuality, racism, and inter-racial relations. She is known for her stories of complicated romances that have strong female voices. The book I read was Bedtime Eyes, which is centered around the relationship between a Japanese woman and a black American man. It is explicitly erotic, manipulative, and violent. She is unsettling to read perhaps because of the amount of black exoticism and objectification laid bare. I have heard that Trash also has a similar interracial relationship.

Yōko Tawada 多和田葉子

Yōko Tawada (1960) was born in Japan and now lives in Berlin, Germany. She writes in both Japanese and German and has awards such as the Akutagawa Prize, the Tanizaki Prize, and the Noma Literary Prize in Japan as well as the Goethe Medal and Kleist Prize in Germany, and a National Book Award in the US.

She is one of the Japanese writers with more translations that include Where Europe Begins, The Bridegroom Was a Dog, The Naked Eye, and Talisman to name a few.

Her short stories ‘To Zagreb’, ‘Celan Reads Japanese’, and ‘The Far Shore’ are available online and so is an excerpt for Memoirs of a Polar Bear. Her most recently translated work is The Last Children of Tokyo (UK) / The Emissary (US).

Hiromi Kawakami 川上 弘美

Hiromi Kawakami (1958 – ) has recently been getting quite a bit of attention for English translations. She writes fiction, poetry and literary criticism and has her works adapted for cinema. She is also a recipient of the Akutagawa, Tanizaki, and Yomiuri prizes. The book she is known for is _The Briefcase_and she usually has a section on any bookstore shelf you walk into.

Her books that first caught my attention was Strange Weather in Tokyo and The Nakano Thrift Shop mostly because I wanted to revisit places I used to visit while living in Tokyo. Many of the stories are centred around urban life of women in Tokyo, such as Record of a Night Too Brief. The only book I have read from her so far is her diary (東京日記 卵一個ぶんのお祝い), and I quite enjoy her quirky, light-hearted entries sprinkled with casually scathing remarks.

Check out this Asymptote Journal article of Record of a Night Too Brief.

Yōko Ogawa 小川 洋子

Yōko Ogawa (1962 – ) has published more than forty works of fiction and nonfiction and has also won the Akutagawa Prize. Her stories usually have female protagonists with strong voices. The stories vary and can be grotesque and disturbing — Hotel Iris is explicitly sexual, while her book The Housekeeper and the Professor was made into the movie The Professor’s Beloved Equation. She’s also co-authored “An Introduction to the World’s Most Elegant Mathematics” with Masahiko Fujiwara, a mathematician. The Memory Police has an English translation as of 2019 and if you want to try more stories in one go, you can go for The Diving Pool: Three Novellas.

Yu Miri 柳美里 유미리

Yu Miri (1968 – ) is a zainichi, a Korean born in Japan, but remains a South Korean citizen because the country of her birth will not grant Koreans Japanese citizenship. She joined the theatre after dropping out of high school and is a playwrite, novelist, and essayist. Her novel Furu Hausu (フルハウス) won the Noma Literary Prize in 1996 and Kazoku Shinema (家族シネマ) won the Akutagawa Prize. Her best-selling memoir Inochi (命) about her becoming pregnant with her ex-lover before he has terminal cancer was made into a movie same name.

Yu’s perceived foreign status has made her the subject of public scrutiny and racist backlash, with events at bookstores being cancelled due to bomb threats. Yu’s semiautobiographical first novel titled Ishi ni Oyogu Sakana (石に泳ぐ魚) published in1994 became the focus of a legal and ethical controversy. The publication of the novel in book form was blocked by court order, and some libraries restricted access to the magazine version. After a prolonged legal battle, a revised version of the novel was published in 2002

Tokyo Ueno Station was published in English in late 2019. Gold Rush is also available in English.

Mieko Kawakami 川上未映子

Mieko Kawakami (1976 – ), from what I recall, is one of the few on this list who was born outside of the Kanto area. Unlike a number of the other writers, she was born in Osaka and grew up poor (as opposed to the child of literati or academics). In addition to writing, she was also a singer-song writer, but soon after she transitioned, she won the Akutagawa Prize for her debut novel, Chichi to Ran (Breast and Eggs), which seems to be sadly out of print.

Breast and Eggs as a novella focused on working-class women of Osaka provides another perspective to the often Tokyo-centric well-to-do or middle-class women by other novelists. The Osaka dialect that it is written in has been translated into a similarly rough English by the translator, Louise Heal Kawai. Kawakami’s most recent translated work is Miss Ice Sandwich, also novella-length.

Sayaka Murata 村田沙耶香

Sayaka Murata (1979 – ) has won the Gunzo Prize for New Writers, the Mishima Yukio Prize, the Noma Literary New Face Prize, and the Akutagawa Prize and her only book available in English is currently Convenience Store Woman, which draws inspiration from her own experience working in a convenience store.

Yukiko Motoya 本谷有希子 1979

Yukiko Motoya (1979 – ) has taken a number of other professions before becoming known as a writer, including voice acting, radio DJing, playwriting and stage directing. Her latest publication is a collection of short stories titled The Lonesome Bodybuilder, which falls into the typically strange relationships and blurry lines between fantasy and reality from book reviews_._ The book that won her the Akutagawa Prize, Irui Konin Tan, has yet to be translated into English.

Hitomi Kanehara 金原 ひとみ

Hitomi Kanehara (1983 – ) is known for the novel novel Snakes and Earrings, which she wrote at the age of 21 and garnered her the Shōsetsu Subaru Literary Prize and the Akutagawa Prize, and sold over a million copies in Japan alone. The novel falls into the typically dark, off-kilter style that I associate with Japanese writers. It follows an unstable young woman known as Lui who is fascinated with body modification and decides to split her tongue.

Risa Wataya 綿矢 りさ

Risa Wataya (1984 – ) wrote her first novel Insutoru (Install) in high school and it won the Bungei Prize in 2001. She shared the Akutagawa Prize with Hitomi Kanehara, when she was 19, making her the youngest winner in the history of the title. Her work in contrast to other writers gives a raw insight into the preoccupations of her life at the time of writing — namely high school and young adults. However, after graduating from undergraduate, she joined many other fresh grads and took up part-time jobs at a hotel and clothing store.

Unfortunately, her award-winning debut is available in French rather than English. The only English novel I am aware of is I Want to Kick You in the Back, translated by Julianne Neville.

Woman Critiqued: Translated Essays on Japanese Women’s Writing by Rebecca L. Copeland (Editor), Ei Akitsu, Eiri Takahara, Junko Takahashi, Shun Akiyama, Takako Takahashi, Miyoko Tanaka, Taeko Tomioka

Prizes to watch for Japanese literature include:

- Akutagawa Prize (Akutagawa Ryūnosuke Shō 芥川龍之介賞) – One of the most prestigious prizes

- Naoki Sanjugo Prize (Naoki Sanjūgo Shō 直木三十五賞) – One of the most prestigious prizes

- Izumi Kyōka Prize for Literature (Izumi Kyouka Bungaku Shō 泉鏡花文学賞)

- Noma Prizes (includes new writers, children’s literature etc.)

- The Yomiuri Prize

- Tanizaki Prize (Tanizaki Jun’ichirō Shō 谷崎潤一郎賞)

- Yomiuri Prize for Literature (Yomiuri Bungaku Shō 読売文学賞), with fiction, drama, poetry, essasy & travelogue, criticism & biography, and translation

The other good news is that independent publishers such as Tilted Axis Press and Peirene Press are making efforts to source more world literature to translate into English, giving voices to writers who are esteemed in their home country that extend beyond stereotypical stuff chosen by mainstream publishers.

Translators play a significant part in mediating a story. In many ways, a translated book is a new piece altogether. In this case, I have chosen not to add the names of all the translators, but if you like a particular translation, you should look into the translator’s other works.